bunnywhiskers interview with Roberto Corsi of Penny Records & David Nerattini of La Batteria plus new podcast

Friday, March 25

5pm

Last month I met in Rome with Roberto Corsi from Penny Records and David Nerattini of La Batteria to talk about their new releases, library music and soundtracks!

bunnywhiskers – Penny Records has a new release coming out soon?

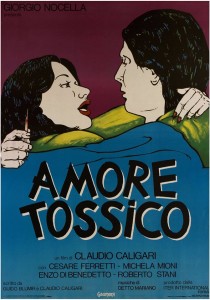

David Nerattini – It’s the soundtrack from a film called Amore Tossico, which is translated as Toxic Love. It’s the story of the junkie generation. In the beginning of the ’80s it was a big political issue that shook the foundation of the youth at that time who were destroyed by heroin.

Roberto Corsi – At that time the streets of the big cities and also the small towns were invaded, flooded with heroin.

bw – What year was the film made?

RC – It was shot in ’81-82 and was released in 1983.

bw – Who was the director?

RC – Claudio Caligari. At the time he was a young director. The idea was to do a documentary but not with a pitying attitude towards the junkies.

DN – It’s from the junkies point of view and there is no moral. It’s just them and their day.

RC – The film received a special mention in the 1983 Venice film festival and was presented also in Cannes, so he had a little exposure. But the language was difficult because they were speaking Roman slang, so it was hard to translate. The soundtrack to this movie was done by a composer / arranger Detto Mariano. It’s all done on a Fairlight synth.

DN – This synth was one of the first samplers.

RC – It was an avant-garde instrument. Detto Mariano had a long career and he started out in the Adriano Celentano gang as a songwriter.

DN – Celentano was like an Italian Elvis. He brought the first rock and roll to Italy. He was quite a character, tall, strange looking and strange singing. In Italy he is an institution.

RC – Celentano had a gang like Sinatra had the Rat Pack.

DN – It was his clan.

RC – A clan that was all songwriters and artists.

DN – Like a little factory. And Mariano was one of his main arrangers. Then in the 1970’s, when this pop music was failing, he moved to soundtracks.

bw – It’s interesting that he moved from pop music to soundtracks. I was under the impression that that was unusual.

DN – There were a few people that did, but mostly they were coming from serious music. You can actually divide Italian composers into two streams. There are the contemporary classical based composers like Ennio Morricone and Bruno Nicolai – mathematical and rational. And then there are the people coming from a pop, jazz background like Piero Piccioni and Armando Trovajoli. They were the first ones to put jazz music in an Italian soundtrack. Both had a classical music background but their heart was in jazz. Trovajoli was doing soundtracks and doing jazz trios on the side. Piero Umiliani was actually the first one to try a straight jazz soundtrack with no orchestra. Detto Mariano was one of the few coming from a straight pop background. His real name was Mariano Detto, but he switched it. We don’t know why.

RC – Although it has an interesting sound when switched. Detto in Italian means “I said,” so when it was switched it means “I said Mariano.” So this soundtrack has never been released. It’s a very weird soundtrack and it was composed with the help of an actual drug expert. Mariano didn’t know anything about the world of drugs, especially heroin, so the director brought in a drug expert. So the expert told him when he was composing which sounds would be perfect for a heroin high or “that’s not the right sound for an overdose.”

bw – And the drug expert was….

DN – An ex-junkie. The movie was made like that! All the consultants were real life junkies. All the shots were real. Of course, they weren’t using heroin, they were using distilled water or something, but they were actually shooting. There’s an almost splatter scene where this girl is shooting herself in the neck. It was a very rough movie and the music sounds just like the movie, very harsh.

RC – It’s a mixture of, say, Suicide, Carpenter, Throbbing Gristle and some industrial stuff. Very tough.

DN – It’s hard to listen to.

RC – The record will be available in May and will be on blood red vinyl, of course. Along with this will be a tribute by La Batteria.

DN – We rearranged and replayed the eight of the tracks. La Batteria is drums, bass and guitar and the original soundtrack is early ’80s keyboards. The music is stunning and we thought it would be perfect for us. The original is called Amore Tossico and ours is called Tossico Amore – the reverse. Also, the cover will be a reverse of the original cover.

bw – On the four criminal compilations there are a number of unreleased tracks. How did you find those?

DN – I work for one of the big library catalog publishers and I was in charge of the back catalog. So I went through all the masters and found some that had never been released. No one had any clue why they hadn’t been released.

bw – Have you found more material that hasn’t been released?

DN – We just moved our office and found two or three boxes with master tapes and we don’t know what’s inside!

bw – Do you know anything about Marcello Giombini and his unreleased material?

DN – He had a house full of stuff that just disappeared when he passed away. Giombini made a lot of music for the Vatican. He made many recordings of masses, like rock groups playing Christian songs.

bw – That’s surprising because he did all those really sleazy soundtracks like La Bestia Nello Spazio.

RC – The thing is that those musician composers were doing whatever. They could play half the day doing sleazy porn and then later play more classical stuff. It was filling their schedule of the day. That’s why they had a lot of nicknames. They would have a contract with the National TV, so they were not supposed to do other records.

DN – It was a very complicated world.

bw – So it seems like a lot of these guys wore many different hats and were kind of guns for hire.

DN – Alessandro Alessandroni was the same way. He was a singer and guitar player, but ended up doing whatever he had under his hands. Whistling for Morricone and all the Italian soundtracks.

RC – He still whistles pretty good.

DN – I secretly want to involve him in the next La Batteria album with the whistles. He is a very good, kind, sweet man.

bw – What does the name La Batteria mean?

RC – You can translate it in a number of ways.

DN – One translation is the drums. La Batteria is also a set of things, like pans. And in our case it is also slang for a gang. In Rome when a gang pulls a heist….

RC – Or a bank robbery…

DN – They would call themselves “la batteria.” We use it with a triple meaning, actually.

RC – Because there is a sexual meaning as well – gang bang.

bw – How did you get started?

DN – We got started by chance. I work for Flipper Music and I’m in charge of two libraries. I noticed that a certain kind of Italian sound – soundtrack, rock, prog – was coming back. Especially when I heard a band called Calibro 35 at the end of a Bruce Willis movie, I thought there must be something here. Then I thought it would be nice to do a library record just like we used to do in the 1970s, no computers involved and only vintage instruments using the kind of composing with a classical background, but mixing in funk and psychedelic.

RC – With the Italian attitude!

DN – With the Italian weird take! Eccentric. So I said, “Let’s do it like we used to,” and I contacted a few friends that could play and understand what I was looking for. We wrote twelve tracks together, went into the studio, started recording and had a lot of fun. And I said, “Let’s do a couple of gigs and see what happens,” and people were really into it.

bw – And you have a new record coming out.

DN – Yes, it’s a free download EP with remixes and two unreleased tracks.

RC – It comes out March 4th.

DN – We have hip-hop remixes, techno remixes. Since it started as a library album there was a lot of stuff we couldn’t do because it had to be a certain format – no songs longer than four minutes, no solos. So the fun starts now.

bw – I wanted to asked you about a few library composers that were on your compilations. One is Daniela Casa.

RC – We released a full album of hers called Società Malata on Penny Records.

DN – She started as a guitar player in the 1960s, playing in clubs, and she had a small career as a pop singer with a few singles. When she didn’t make it as a singer, she actually started teaching and she was my guitar teacher when I was a kid, from six to nine. And those were the years she was making those records.

bw – There’s a song of hers on the compilation that I really like called Black Sabbath.

DN – That was an unreleased track and Black Sabbath probably wasn’t even the right title, but only a working title.

bw – That song has a pretty heavy sound.

RC – That’s a ripoff of a Black Sabbath song.

bw – And that’s her playing that heavy guitar?

DN – That’s her playing in all of those songs. She was a great guitar player. She was a rocker! Very cool and very sweet.

bw – There’s another song of hers I like – Occultismo – a vocal song.

DN – She did many things. She did the rock stuff because she liked it very much. When she could, she plugged the electric guitar in – fuzzy! I remember her playing in her little studio at home very loud, like guitar hero. But she was a classical composer, too. She played piano and synthesizers. And her husband was Remigio Ducros, a library composer as well.

bw – Were Daniela Casa and Remigio Ducros involved in the counterculture here in Rome?

DN – Yes, Daniela Casa was playing in the main Roman club at the time. It was called Piper Club.

RC – The Piper Club was this club where all the pop came out in the sixties. For example, Patty Pravo was a famous singer who performed there.

DN – Patty Pravo was the center of the early counterculture. Not the political counter culture, but the pop one.

RC – Like fashion and turning to rock music.

DN – Like swinging London – trying to recreate that in Rome. That kind of style – like The Bag O’Nails. All the new bands played there like Pink Floyd and The Who. Patty Pravo was like the queen.

RC – She was like our Francoise Hardy.

bw – And Daniela Casa and her husband were involved in that scene?

DN – Yes, Remigio Ducros was playing keyboards with Lucio Dalla and Daniela Casa was playing with this character called Gepy. He was a very fat R & B singer. They had a duo called Dany and Gepy. She was playing guitar and he was singing.

bw – How many library records did she do?

DN – Maybe twenty. Most of them are lost.

bw – Another composer I think is really interesting is Fabio Fabor.

DN – His real name is Fabio Borgazzi. Most of the nicknames among library musicians are rehashing of their real names.

bw – Why so many nicknames among these musicians?

DN – Sometimes they didn’t want people to know about projects, sometimes they couldn’t do it because of contracts. Sometimes you find a record in someone’s name, but it is actually somebody else. They would record under the other person’s name and split the money. It was like a jungle, especially in the library stuff. And it was like that in pop music, too. So it’s kind of hard to know who did what. But once you understand this you can begin to tell someone’s sound when you hear it. I can tell an Alessandro Alessandroni record in ten seconds. You listen to a record by Stefano Torossi and it sounds like another guy and eventually you find out it actually is that other guy!

bw – My ear isn’t that good yet, but hopefully it will be one day! But back to Fabio Fabor. I think he has a really interesting sound.

DN – He’s probably one of the people that made more library records than anybody else. He must have made hundreds of library records with different names so it’s hard to track them. Some with his real name Fabio Borgazzi.

RC – But most of them as Fabio Fabor.

DN – Others with strange names he used once or twice and then dropped.

bw – So it is hard to sort it out and perhaps some of them have been lost.

DN -Yes, but his family kept most of his stuff so I have seen some recent releases of his work that I think they got directly from his family.

bw – That means there might be more Fabio Fabor releases coming?

DN – Yes, I’m sure.

bw – Who are some library musicians that may be less well-known but are worth listening to?

DN – I have two names of musicians that made many records. One is Rino de Filippi. He was quite good and extremely versatile. Another is Antonio Riccardo Luciani or A. R. Luciani. He was a teacher at the Conservatory in Florence and also did many great library records in the 1970’s. Daniela Casa and Remigio Ducros worked for one or two library labels but Rino de Filippi and A. R. Luciani worked for every single label of the labels.

bw – Another library composer that I find interesting is Egisto Macchi.

RC – Egisto Macchi, like Ennio Morricone, was in Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. There have been many records by him released.

DN – He always did very avant-garde stuff. In every library record you can usually find one or two jazzy, pop or loungey tracks. Egisto Macchi, no. I think maybe one or two tracks for a cop show weren’t avant-garde. Like Morricone, he studied at the conservatory with Goffredo Petrassi who shaped most of the mathematical composers.

bw – I’m wondering about influence the older composers had over the younger composers….

DN – The early composers, like Goffredo Petrassi, did not do many soundtracks. Petrassi did maybe one or two, but he was not really interested in that because he was a serious composer. Then there were second generation of composers, the Trovajoli, Morricone, Piccioni generation, who did soundtracks. The third generation were Frizzi, Bixio, Tempera and the De Angelis brothers who were session musicians for the Trovajoli, Morricone, Piccioni generation. For example, when you hear a twelve string guitar 99 percent of the time it was one of the De Angelis brothers.

bw – What went into the making of the Italian style?

DN – Until the 1970s Italy had a special, distinctive character in making music, we did music our own Italian way.

RC – And then Italian musicians were listening to American music like Quincy Jones.

DN – But they didn’t replicate it. They did it their way and they created that sound that is the best! They knew how soundtracks were developing in the States and they were adapting some of those things to what they were doing. They put something of their own in it and it became a style. Like Morricone – the cliche for any Western in the United States is Morricone. To me it’s the most funny thing in the world that an Italian wrote the cliche for the Western movies. A loud guitar wasn’t used in a Western before Morricone.

RC – Before that the compositions for American Westerns were these big orchestral things.

DN – And so all these composers had something special. Trovajoli and Piccioni could do something like Quincy Jones the Italian Jazz way.

RC – For example, Micalizzi – you can tell he was listening to Quincy Jones but what was coming out was not Quincy Jones.

bw – So much of the music for Italian B movies is wonderful.

DN – Composers were able to take chances because they had a lot of work to do and they were able to experiment inside their work. Nobody cared and there was no director saying, “Oh this one’s bad.” They were just working fast.

RC – There were no boundaries.

DN – Especially for B movies. They had no time and music was the last thing. The composers were doing whatever they liked and in library the same thing. They exploited library and soundtracks for their own creativity. They didn’t care what was right or wrong, they just did it. Very Italian, “I don’t care.” That “I don’t care” sometimes lets you do great things because you’re working outside of the box. It was a job and they just had to do it for a cheap price. What’s missing now is young composers have no chance to experiment doing the job. They’re experimenting at home so they don’t know if it’s right or wrong and no one tells them if it works or not.

bw – How do you feel the old soundtrack music influences your work?

DN – We thought for twenty plus years the only way to do music was like the English and the Americans. So we kind of erased all the work that was done in the previous decades. All that work was forgotten. We were trying to be like Americans and that’s stupid because we had something. Now thanks to what’s coming from outside of Italy, because Italy is always late, we discovered we had this music. And it still sounds fresh and it resonates with the times we are living in. The kind of tension we had in the 1970s is coming back so that kind of music has a role in our lives. And we relearned with La Batteria that there was an Italian style of playing every kind of music. It was in our hands and our hearts and we didn’t know. In La Batteria we realized we could play the same fun grooves not trying to be an African American drummer, but do the same thing our way. There’s a language to it and there are Italian drummers to look to. For example, how did Vincenzo Restuccia (who played for Ennio Morricone) do it?

bw – Could you talk a little bit about the Italian soundtrack style?

DN – We had a balance between the Italian way, which was the shortest and cheapest way, and the need for something artistically good. If the movie isn’t good, you can’t sell it. So the people that were working knew what they were doing. Maybe they had a small budget and only twenty days to make a movie, but they were professionals. What was coming out wasn’t always the perfect movie or the perfect soundtrack. In fact, many soundtracks you can hear all the mistakes they are playing because they had no time. Like in Mark il poliziotto, on the first track you can hear the bass player hitting the wrong notes and the saxophone player not in tune. They were working fast but good. Do it in ten minutes and say, “That’s pretty good.”

RC – As we say, buona la prima.

bw – Good the first time!

DC – It was a balance between robbery and pure art. Now it’s more robbery than pure art.

bw – Do you think there are some other newer bands that are influenced by the old guard?

DC – Of course. Calibro 35 is the first band that started this.

RC – They are also very good musicians.

DN – They started doing covers of the great Morricone and Piccioni soundtracks.

RC – And then they evolved into their own style and sound.

DN – Very aggressive funk.

RC – There is also a very good band called Squadra Omega. They are more psych. Another one I like a lot is C’Mon Tigre.

DN – Also, Fuzz Orchestra.

bw – So the old style is trickling down.

RC – We have always been looking at the other world. We have kind of a colony attitude.

DN – Meanwhile, there are so many people outside of Italy that try to copy us. It is so strange that we are not copying ourselves. So with La Batteria and the other bands we are trying to put back that Italian touch. We just forgot about it! I had been doing hip-hop – the most American thing ever! Then I discovered that people in America were sampling Italian stuff. I realized there’s something wrong here. I knew everything about the Bronx but didn’t know anything about people around me. I realized after many years that Daniela Casa was actually my guitar teacher and a small genius. Can you believe it? So I went back to relearn it. We all went back to relearn it and we found we had an imprinting. It was the sound we heard as kids. We know that sound because it’s in our head and hearts and brains. With La Batteria, that was the main reason we formed the band and played. We realized we had a vocabulary and a whole world to explore. We can play any kind of music from extreme heavy metal to avant-garde and we can play it our way….

bw – The Italian way!

DN – For a musician that’s an epiphany. And I had it all along.

Penny Records – http://www.forcedexposure.com/Labels/PENNY.RECORDS.ITALY.html

Penny Records Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/Penny-Records-231728416902803/?fref=ts

La Batteria – http://www.labatteriaband.it/

La Batteria Bandcamp – https://labatteria.bandcamp.com/album/fegatelli

Also new bunnywhiskers podcast featuring music from Amore Tossico, Screamers, The Toolbox Murders, Burial Ground, Contamination and more –